Herat

©1970 Ruth and Franklin Harold / The Friday Mosque, HeratOf the chief cities of medieval region of Khorassan, only Herat still presents a substantial and lively city on its original site, with sufficient architectural remains to convey a sense of continuity with its time as the capital of the medieval Timurid Empire.

Herat owes its existence to the Hari Rud, the river flowing past the city just a few miles away. The river rises in the mountains of Ghor to the east, turns north along the present border with Iran, and eventually vanishes in the sands of the Karakum desert. Along the way it sustains a narrow but fertile oasis, cultivated continuously since antiquity, and flanked by some of the richest grazing grounds in all of Central Asia. Herat was also a crossroads of commerce: routes ran north along the Hari Rud to Merv and Bukhara, south to Kerman and into Iran, east to Balkh, Samarkand and China, and west to Nishapur and Constantinople. Herat lost its pivotal position in the 1880s with the construction of the Trans-Caspian Railway, which passes far to the north. But it remains a place where the manifold peoples of Central Asia mingle - Tadjik farmers, Turkoman nomads, Uzbeks and Hazara (and in the 19th century there were also Hindus, Armenians and a sizeable Jewish community).

Herat’s eventful history is particularly well documented, thanks chiefly to a succession of local historians. The city first appears in Achaemenid records under the name Haraiva. Alexander the Great conquered it and built a fortress. The Sassanians ruled the city until the Arabs first invaded in 651 AD, although it was lost and regained several times before the conquest was settled. Herat subsequently became part of the dominions of the Samanid, Ghaznavid, Seljuq and Ghorid dynasties from 10th to 12th centuries AD. It was clearly a substantial city in those days: both Istakhri and Ibn Hawkal, geographers of the 10th century, describe a prosperous town with ample water and an unusual square plan (still visible today). The city was guarded by strong mud walls with four gates and a central citadel. It held a large Friday Mosque and, in the suburbs, both a fire temple and a Christian church.

The Mongol conquest of Herat in 1221 seemed to bring destruction and disaster. The city surrendered after a short siege, but a popular revolt a few months later resulted in the entire population being put to the sword. The network of irrigation canals was destroyed, the whole region devastated, and desolation reigned for decades along the Hari Rud.

Later Mongol khans ruled indirectly through local governors, and it was under one of these, the Kart dynasty (1245 to 1389 AD) that the groundwork was laid for Herat’s revival. They restored canals and bridges, rebuilt the walls and refurbished the great mosque. The city was conquered by Tamerlane in 1381 AD, and thus became part of the Timurid Empire that stretched from China into Iran.

The Timurid period was one of social and economic growth for Herat. The upturn began with the appointment of Timur’s youngest son, Shah Rukh, as governor of Herat (1397 AD). A pious and scholarly man who preferred the rewards of peace to wider conquests, he seems to have been a capable leader, and became supreme ruler upon Tamerlane’s death (in 1405 AD), and held the vast empire together for the next fifty years with Herat (rather than Samarkand) as its capital. Herat reached its apogee under Husayn Baikara (1470 - 1506 AD), when the splendour of the city and the court were celebrated across the Muslim East. Babur, who went on to conquer India and to found the Mughal dynasty, was a nephew of Sultan Husayn and visited Herat just before the latter’s death. Years later he paid tribute in his autobiography: “The whole habitable world had not such a town as Herat had become under Sultan Husayn Mirza... Khorasan, and Herat above all, was filled with learned and matchless men. Whatever work a man took up, he aimed to and aspired to bring it to perfection”.

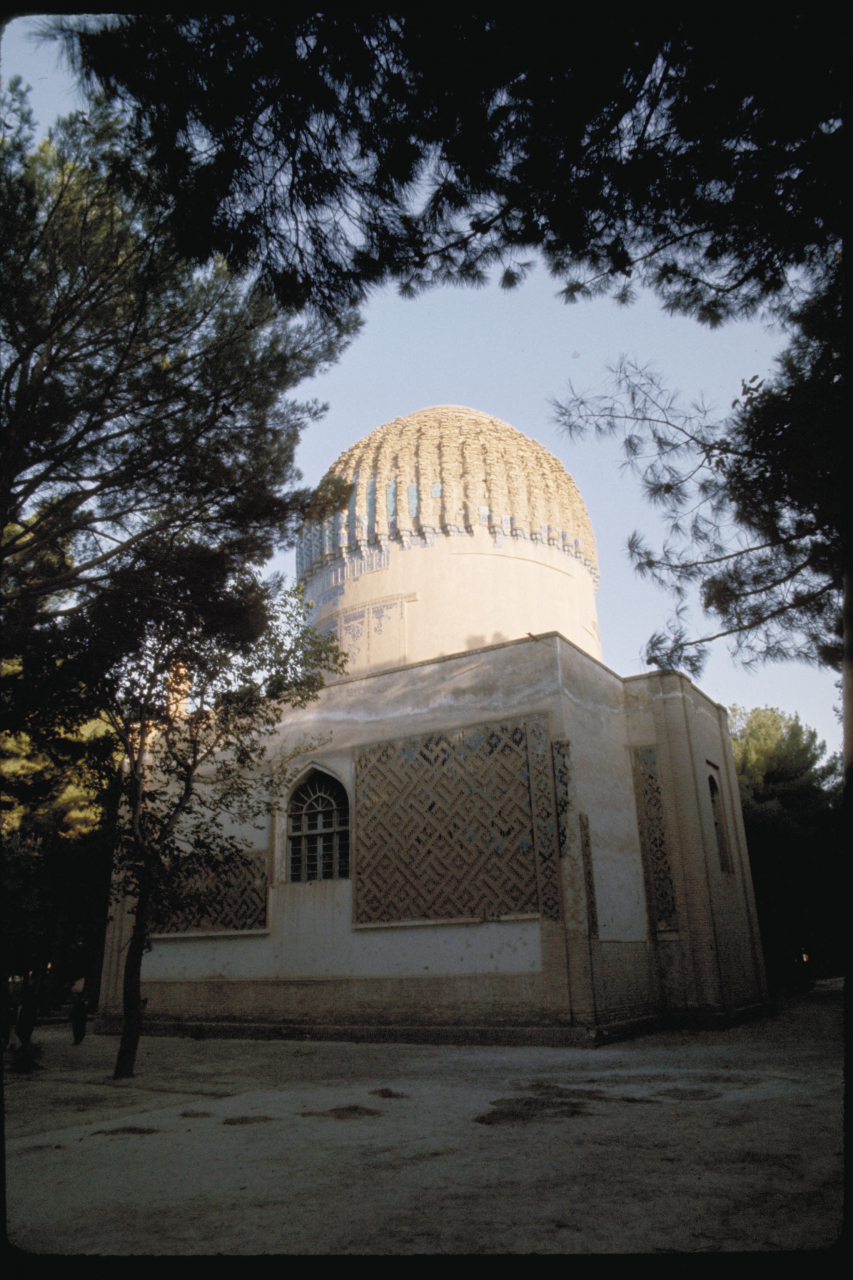

The majority of Herat’s surviving monuments were constructed or renovated during the 15th century. Gowhar Shad, the wife of Shah Rukh, sponsored her own magnificent mausoleum in Herat as well as the adjoining Musalla, a complex of mosque and seminary of which only a few minarets remain. All her buildings are famed for the brilliance and perfection of their glazed-tile decoration. Husayn Baikara presided over a court filled with noted poets, scholars, musicians and painters. Behzad, still considered Iran’s most accomplished painter of miniatures, was a native of Herat and did much of his finest work there. The traditions laid down in 15th-century Herat continued to inspire the painters and architects of Iran and Mughal India for generations to come.

However, north of the Oxus, the Uzbeks were on the rise; already Samarkand had fallen to them, and a year after Sultan Husayn’s death in 1506, they invaded and conquered Herat. The Timurid Renascence was over, and Central Asia slid back into turmoil.

The Uzbeks did not hold Herat for long. It fell to the rising power of Safavid Iran, which imposed Shi’ism on a predominantly Sunni population. No longer the centre of an empire, Herat remained an important regional capital. Iranian rule lasted until 1746, when the city was incorporated into the state of Afghanistan.