Balkh

©1970 Ruth and Franklin Harold / Mazar-e-Sharif (the Tomb of the Exalted)Balkh is an ancient city, with a 2500-year long history, situated on the plain between the Hindu Kush Mountains and the river Amu Darya (historically known as the Oxus) in the north of Afghanistan. Known by Arab conquerors as Umm-al-belad, the ‘mother of cities’, Balkh lay on the major Silk Road routes that ran between east and west. The city’s history was illustrious until Ghengis Khan and his Mongol hordes wreaked destruction in 1220; Balkh never fully recovered, and eventually faded into a village, whilst the seat of government shifted by 20 kilometers south to Mazar-e-Sharif.

Geography is an important factor in the explanation of Balkh’s prominence. The city sits on an alluvial fan built up by the Balkab river, well suited to irrigation. The region, called Bactria in ancient times, was renowned for its grapes, oranges, water lilies, sugar cane, and an excellent breed of camels. Most significantly, several natural trade routes intersect at Balkh. From there, caravans could follow the well-watered foot of the mountains westward towards Herat and Iran, or across the Oxus to Samarkand and China. The valley of the Balkhab still gives passage to Bamiyan and thence to Kabul; of all the routes across the Hindu Kush, this is the most westerly and the easiest to cross for a loaded merchant caravan. As a result, craftsmanship and trade flourished in Balkh, as well as theology, philosophy and the arts. On the down side, Balkh was rich but not powerful, and became the envy and the prize of more warlike neighbours.

Always a place of importance, Bactria and its capital city figure prominently in the annals of historians and travellers. It first appears on a list of the conquests of Darius, who incorporated it into the Achaemenid Empire. Zoroaster taught here, perhaps in the 6th century BC, and the Zoroastrian faith became the state religion of the Achaemenids and later of the Sassanians. Alexander took Bactria in 329 BC, and made it his base for conquest and the amalgamation of the Greek and Persian civilizations.

Bactria was later annexed by the Kushans (129 BC), whose large and powerful empire stretched from Central Asia deep into India. At this time, the lands through which the caravan routes passed were divided among a few stable states which submerged their differences in the interests of trade, and Balkh flourished at the crossroads as a depot point for the world’s luxuries. With the merchants came monks preaching the new religion of Buddhism, and Balkh became a centre of worship and learning, and was famous for its temples and monasteries. By the time the Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang passed through Balkh (in 630 AD) on his way to the fountainhead of Buddhism in India, the city had become part of the Sassanian Empire.

The times that followed were turbulent ones in Central Asia. Balkh changed hands repeatedly between Arab, Persian and Turki rulers, and was sacked more than once, yet it continued to flourish. The Arab geographers Yaqubi and Moqaddasi (from the 9th and 10th centuries AD) depict Balkh as it was under Samanid rule, when Bukhara was the centre of power. A large and prosperous city some three square miles in area, it held perhaps 200,000 persons. It was surrounded by mud-brick walls pierced by seven gates. A splendid Friday Mosque occupied the centre, and many more mosques were scattered among the dwellings, whilst the fire temple in the suburbs, which Xuanzang had admired when it was a Buddhist monastery, was still noteworthy. The city was home not only to Persians and Turks but also to communities of Jews and Indian traders. It nourished poets and scholars, lawyers and even geographers and astronomers.

The city’s fortunes took a radical turn for the worse however in 1220, when Ghengis Khan chose to make an example of Balkh, and sent one hundred thousand Mongol horsemen to entirely sack and destroy the city along with all its inhabitants. Balkh remained in ruins for a century, and was so described by Marco Polo (1275) and by Ibn Battuta (1333). Revival must have been under way by this point however, as Tamerlane chose Balkh to proclaim his accession to the throne (1359). Tamerlane and his Timurid successors favoured Balkh; they restored the walls and endowed the city with quite splendid buildings, a number of which are still standing, most notably the mausoleum of Khwaja Abu Nasr Parsa, erected in1462/63 in honour of a distinguished theologian and considered one of the finest examples of late Timurid architecture. Also of importance are the walls, battered and weather-beaten but still sixty feet high in places, built in Timurid times (14/15th centuries) upon foundations that appear to go back to the Kushans and possibly further.

The city was subsequently fought over by Uzbeks, Safavids, Mughals and eventually the Durrani Shahs of Afghanistan, but slowly declined in its importance. In 1866, the administrative centre of Afghan Turkestan migrated to nearby Mazar-e-Sharif.

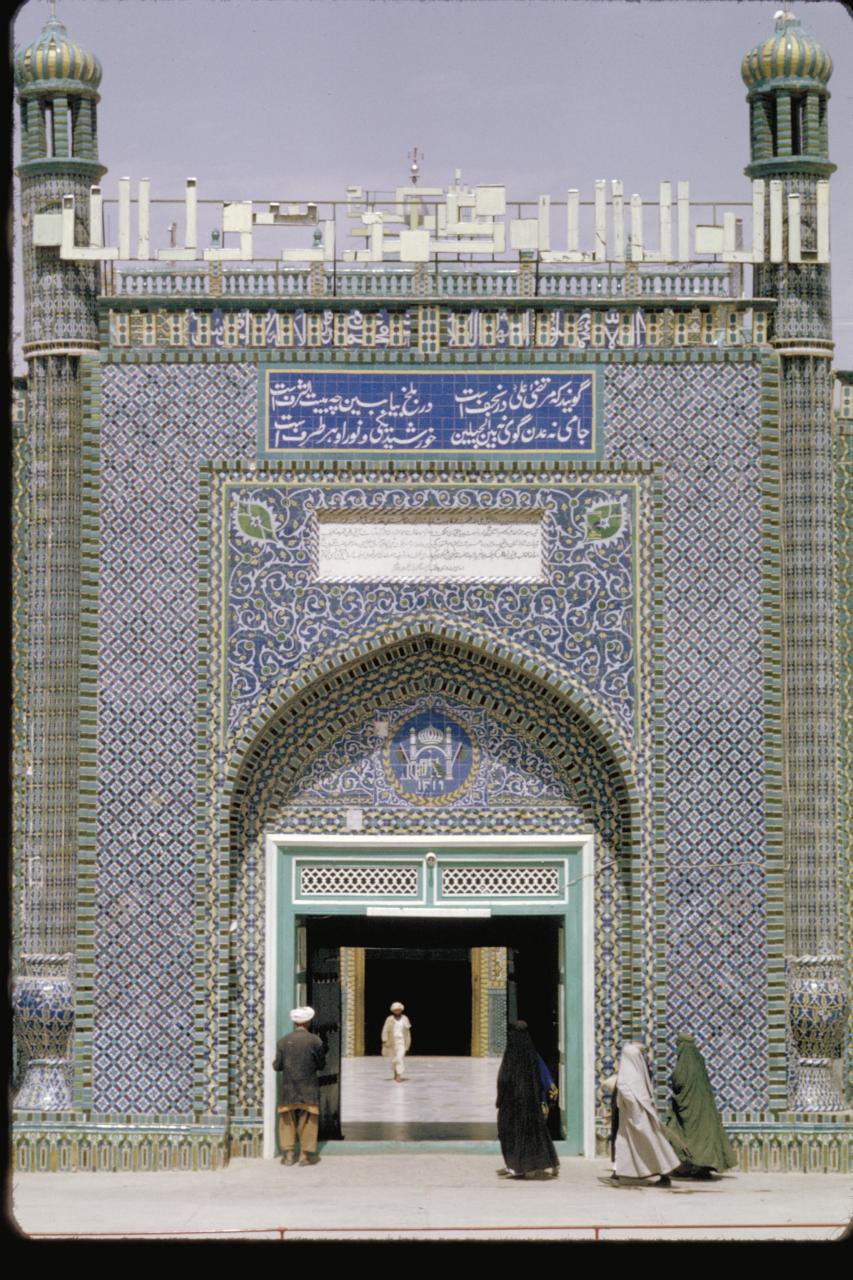

Mazar-e-Sharif (or Tomb of the Exalted), is home to the great shrine of the Sharif Ali, which lent the city its name. Hazrat (The Noble) Ali is one of the central figures of Shia Islam, and was the Prophet Muhammad’s cousin and son-in -law, and eventually became the fourth Caliph. But his reign was marred by discord; he was assassinated in 658 AD, and according to orthodox tradition, was buried in Najaf, Iraq. Afghans believe otherwise: the body of the slain Caliph, tied onto a camel’s back, was carried out to Turkestan and buried in a secret location. Five hundred years later the grave came to light and a shrine was built over it. Ghengis Khan levelled it, but Ali’s sepulchre was rediscovered during the reign of Husain Baikara, the last Timurid Sultan of Herat, who erected a grand mausoleum on the site in 1481 AD. This is the building, many times restored and re-decorated, that still stands on the site, with its two domes, large courtyard and blue tilework making it one of the most spectacular buildings in Afghanistan. Pilgrims continue to flock to the tomb, and many thousands come here each spring to celebrate Naoruz, the Persian New Year.