The following article is authored by Diahhadi Setyonaluri, Rachmat Reksa Samudra, and Muhammad Faisal.

Inequity in health systems has become the most significant challenge in the effort to curb the COVID-19 pandemic. Pre-existing social, cultural, economic and, importantly, health care inequalities limit equitable access to COVID-19 testing, treatment and vaccinations. The pandemic feeds off these disparities when it comes to the most marginalized populations. Such conditions limit not only their access to health care services but also the quality of the health care services that they do obtain (Samudra & Setyonaluri, 2020).

Like many countries, Indonesia has faced challenges in delivering an equitable response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The second wave of the coronavirus in June-August 2021 revealed the vulnerability of Indonesia's health system. COVID-19 patients needing immediate and intensive care were flooding hospitals and local public health care facilities. The surge also led to an alarming shortage of oxygen and medicine. Overall, this wave rapidly increased Indonesia’s fatalities to 117,000 cases, with a total of 3.8 million confirmed cases by mid-August 2021 (Ministry of Health of Indonesia, 2021a).

Indonesia has also had a relatively slow pace of vaccination rollout compared to other countries in Asia. The government now aims to inoculate 208.3 million individuals, 70% of whom should be reached by the end of 2021. By mid-October 2021, the vaccination programme reached 50% of the overall target. However, the pace of vaccinating marginalized populations remained slow. For example, the immunization coverage (first dose injection) for older people reached only 35%, while other marginalized groups reached 45% (Ministry of Health of Indonesia, 2021b).

COVID-19 monitoring often overlooks the disparities of cases and vaccination rates across Indonesian regions. Areas with a high proportion of poor and vulnerable populations, particularly in eastern Indonesia, may under-report cases of COVID-19 due to limited access to health care services and workers. Poor access can also inhibit testing, tracing, treatment and vaccination rollout.

Inequality of health care services hinders a timely response for marginalized populations during the COVID-19 pandemic

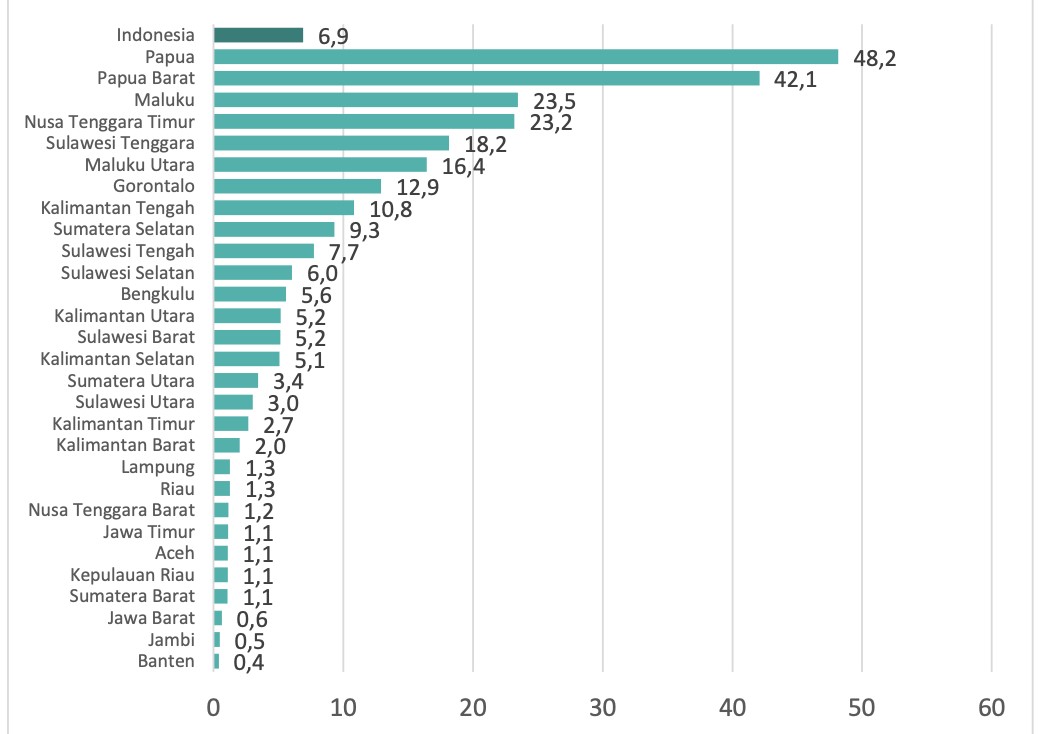

Unequal distribution of health care facilities and workers complicates marginalized populations’ access to health care services related to COVID-19 infection and other concerns. Public health facilities, hospitals and health care workers are concentrated in Java Island, while regions in eastern Indonesia have the largest share of public health facilities without medical doctors. This localized lack of medical doctors is worrisome because a relatively high percentage of the poor population in these regions rely on public health facilities for outpatient care [1].

Figure 1. Share of PUSKESMAS (public health care facilities) without General Practitioners by provinces, Indonesia, 2020

Source: Kementerian Kesehatan (2020) Data Dasar PUSKESMAS

Indonesia has a low testing capacity, which is due to the low amount of laboratories and competent laboratory workers. As of 20 August 2021, there are 795 laboratories for COVID-19 testing, which are concentrated in Jakarta and West Java. It is reasonable to have more laboratories in areas such as Jakarta and West Java since they have high rates of COVID-19 cases. However, this may weaken testing, tracing and treatment in other areas.

Testing is additionally complicated for many people since the tests are often unaffordable. The high cost of testing is clear: PCR tests account for 30% of the per capita expenditure for the population at the highest income quintile and 80% for those in the following two income quintiles [2].

Figure 2. Number of Laboratories for COVID-19 testing by July 2021

Source: Memo of Head of Research and Development Department of the Ministry of Health Number HK.02.02/II/4491/2021. Downloaded from: https://www.litbang.kemkes.go.id/laboratorium-pemeriksa-covid-19/.

Vaccination progress is unequal across provinces in Indonesia. DKI Jakarta, Bali, Riau Island, Yogyakarta, and North Sulawesi led the vaccination progress and are currently above the national average for vaccination rates. Yet the pace of vaccination across regions remains unequal, due in part to the disparity in health care facilities and workers who are capable of performing COVID-19 vaccinations. The presence of vaccine-hesitant groups who refuse to be inoculated or lack information about the vaccination is also an issue in accelerating vaccination coverage (Ministry of Health of Indonesia et al., 2020).

Figure 3. Relationship between vaccinator and dose 1 administered, as per 21 July 2021

Source: Ministry of Health, calculated by authors. Note: Dose 1 administered is based on 25 July 2021 data.

Meanwhile, there have been innovative methods of reaching and increasing the vaccine coverage of vulnerable populations across regions – from massive vaccination programmes at public places to door-to-door vaccinations. However, vaccination progress of varied vulnerable groups is unclear, as the only disaggregated information available corresponds to public health workers, public sector workers, the elderly and youth aged 12-17. The absence of disaggregated data makes it difficult to define ‘vulnerable populations.’ This may hinder the effort to reach the vulnerable via vaccination programmes since definition allows people to be identified, located and targeted (CISDI & PUSKAPA, 2021).

Lessons learned 1.5 years into the pandemic: Close the gap of health care services

Despite diverse and large-scale policies, more efforts are needed to improve the inclusion of vulnerable populations. Women, older people, children, people living with disabilities and indigenous people can still be left out of vaccination due to pre-existing social and economic inequalities. Limited testing weakens efforts to provide timely and inclusive support for marginalized populations affected by COVID-19. Based on our observations of 1.5 years of Indonesia’s pandemic response, we have drawn three strategies:

- Continue strengthening the health system across Indonesia. Addressing the unequal distribution of health care facilities, health workers and laboratories/their human resources would improve marginalized populations' access to timely, reasonable and quality testing and treatment of COVID-19 and future disease outbreaks.

- Refocus the vaccination programme on marginalized/vulnerable populations. This can be done by providing clear guidance in defining vulnerable populations, implementing varied methods in collaboration with community volunteering, and providing assistance for vulnerable people in need of COVID-19 testing and treatment.

- Improve databases and use disaggregated data for better targeting of vaccinations and social assistance disbursement.

Have you seen?

Data equity – there is no hiding

Apply research skills to new data, transform developmental effectiveness

Treat data like you treat infants – signals and empathy are key

Invest in knowledge, use it to rebuild

Partner on data to make it work for public good

References:

CISDI & PUSKAPA, 2021. Policy Inputs to Ensure Access of Vulnerable Groups to COVID-19 Vaccination in Indonesia. Center for Indonesia's Strategic Development Initiatives (CISDI). Available at: https://cisdi.org/id/open-knowledge-repository/policy-paper/masukan-kebijakan-untuk-memastikan-terjaminnya-akses-kelompok-rentan-p....

Ministry of Health of Indonesia et al., 2020. UNICEF. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/indonesia/media/7631/file/COVID-19%20Vaccine%20Acceptance%20Survey%20in%20Indonesia.pdf.

Ministry of Health of Indonesia, 2021a. COVID-19 Dashboard. Infeksi Emerging. Available at: https://infeksiemerging.kemkes.go.id/dashboard/covid-19.

Ministry of Health of Indonesia, 2021b. Vaksin Dashboard. Vaksinasi COVID-19 Nasional. Available at: https://vaksin.kemkes.go.id/#/vaccines.

Samudra, R.R. & Setyonaluri, D., 2020. Inequitable Impact of COVID-19 in Indonesia: Evidence and Policy Response. UNESCO Inclusive Policy Lab. Available at: https://en.unesco.org/inclusivepolicylab/sites/default/files/analytics/document/2020/9/200825_Policy%20Report_Inequitable%20Impact....

Notes:

[1] Based on our calculation from SUSENAS March 2020.

[2] Based on SUSENAS March 2020: the average per capita expenditure for the households from the lowest 40% of income distribution was IDR 550,858, while for the middle 40% was IDR 1.1 million, and for the top 20% was IDR 2.8 million.

….

Diahhadi Setyonaluri is a researcher and a lecturer at the Department of Economics University of Indonesia. She has been working in the area of gender equality and social inclusion in Indonesia.

Rachmat Reksa Samudra is a researcher at Lembaga Demografi FEB UI. His research interests are labor, poverty, social protection, and gender analysis. He received a Master of Arts in Economics degree from University of Hawai'i at Manoa and a Bachelor of Economics degree from Universitas Indonesia. He has contributed to various studies published by The World Bank, Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Research Working Paper, and National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

Muhammad Faisal is a research assistant at the demography institute of the Faculty of Economics and Business, University of Indonesia with skills in economic modeling, statistics and econometrics. The field of research that he is involved is related to the fields of public economics and monetary.

The facts, ideas and opinions expressed in this piece are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO or any of its partners and stakeholders and do not commit nor imply any responsibility thereof. The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this piece do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.