The following article is authored by Katharina Bohnenberger.

- The environmental impact of our economy is largely determined by what, how and when we work.

- Greening labour market policies can boost the transformation to an economy within planetary boundaries and free people from having to work at the expense of future generations.

- The climate crisis and employment crises cannot be solved separately, which therefore requires integrated solutions like green labour market policies.

Fridays, many workers go on climate strike to fight for their future. Mondays, they return to their workplace. Some of them will question what they are actually working for: Am I contributing to a world that saves our climate? Or am I gaining my income with a “b****** job” (Hansen 2019) – a job that harms people and the planet?

The motivation to contribute to the future of our planet should not be limited to one day of the week, rather it should be acted upon every workday. Labour market services should support us in finding jobs in line with the climate budget.

From “just transitions” to greening employment

Although the timelines of the climate crisis and the employment crisis triggered by the pandemic overlapped, the solutions for the crises were discussed in separate policy agendas. This is a missed opportunity for advancing sustainable welfare because labour market policies can contribute to sustainable consumption and production patterns. Moreover, a climate-neutral economy requires all jobs to benefit, not destroy, our natural environment.

Past actions on “just transitions” concentrated on analysing how environmental transitions can be designed to guarantee social outcomes such as reduced income inequality or poverty eradication. Going forward, the focus should also be on the other side of this relationship – namely, on how employment shapes the ecological footprint of our societies (Hoffmann & Paulsen, 2020). A change in labour market patterns will be required to meet climate targets, meaning that labour policies can be leveraged for a green transformation of society.

Four dimensions that make a job green

Sustainable employment is not limited to green sectors like renewable energy generation or organic agriculture. All jobs impact the environment through four dimensions, namely:

- Outputs – Jobs must be considered in terms of the goods that they produce as well as the services that they provide. Planetary boundaries should still be achievable if everyone were to have their needs met through these goods or services.

- Occupation – When assessing individual jobs, it should be considered whether the tasks target an improvement or harm of the environment. In addition, the ecological footprint of further workplace required activities, such as business travel, should be studied.

- Work-lifestyle – Leading a sustainable lifestyle should still be possible while employed in a job. This means that the consequences of working conditions, such as long work hours, lack of time, and excess income, for developing ecologically harmful practices, should be accounted for.

- Outcome efficiency – Jobs should be compared to those within other companies or sectors, comparing how many resources are required to deliver the equivalent goods and services and provide the same volume of employment.

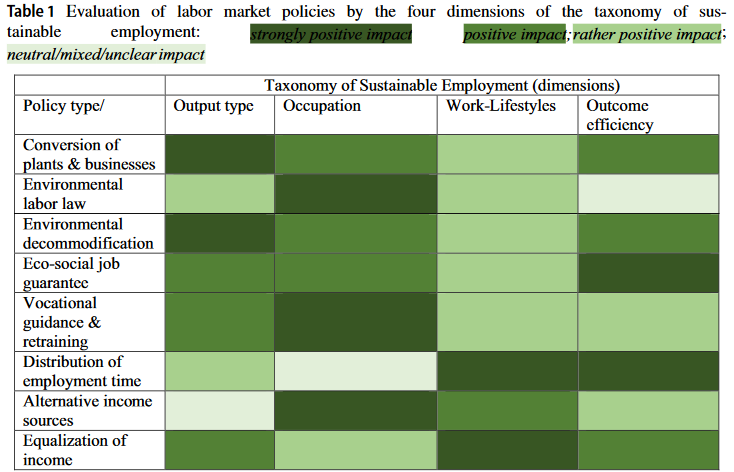

By considering these four dimensions of sustainable employment in their decision making, workers, job centres, unions and ministries can assess the environmental performance of occupations and develop integrated policies for greening labour markets (Bohnenberger, 2022).

Labour market policies for people and the planet

Historically, labour market policies were developed without consideration of the environmental impacts they cause. Recently, however, experts have begun to seek labour market solutions for decarbonization. These fall along 8 different types of labour market policies with potential to contribute to quality work and climate progress:

- Conversion of plants – phasing out fossil business models and replacing them with green products or services.

- Environmental labour law – considering not only the physical health risks of dirty production processes but also the mental health burden of occupying “b****** jobs”.

- Environmental decommodification – replacing income when leaving a job for environmental reasons.

- A socio-ecological job guarantee – reducing the fear of unemployment during the climate transformation and providing universal basic services to society.

- Vocational guidance and retraining – updating the skills of workers with knowledge for a green transition and re-educating them for future-fit professions.

- Work time distribution – sharing the work volume fairer, thereby making a reduction of consumption and production in wealthy countries possible without increasing unemployment.

- Alternative income sources – decoupling household income from employment hours and productivity and linking it to activities that promote a green transition.

Some of the strategies, like green re-skilling or job guarantees, are already well established in certain countries. Others, particularly environmental labour law and alternative income sources, are less explored and open new paths for innovative labour market policies.

The climate crisis can only be tackled by greening the economy, including an ecological mainstreaming of employment. Researchers and policymakers can contribute to this by redesigning current employment and social policies, allowing for the emergence of eco-social policies.

Have you seen?

Sustainable welfare: would a mix of universal basic income and universal basic services help?

Recalibrate - our policies were too heavy on efficiency, too light on equity

EQUITABLE RESET – WHAT ARE OUR (NEW) POLICY OPTIONS?

Welfare systems should be made independent of GDP growth

References

Bohnenberger, Katharina. 2022. Greening Work: Labor Market Policies for the Environment. Empirica, no. 49 (January): 347–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-021-09530-9.

Hansen, B. R., 2019. “B****** jobs” — No-one should have to destroy the planet to make a living. OpenDemocracy. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/opendemocracyuk/batshit-jobs-no-one-should-have-to-destroy-the-planet-to-make-a-living/.

Hoffmann, M., & Paulsen, R., 2020. Resolving the ‘jobs-environment-dilemma’? The case for critiques of work in sustainability research. Environmental Sociology, 6(4), 343–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/23251042.2020.1790718.

….

Katharina Bohnenberger is a Socio-Ecological Economist, Research Assistant, Institute for Socio-Economics, University of Duisburg-Essen.

The facts, ideas and opinions expressed in this piece are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO or any of its partners and stakeholders and do not commit nor imply any responsibility thereof. The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this piece do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.