The following article is authored by Mary Murphy.

- The creation of an eco-social welfare system would serve as an alternative that addresses the dual challenge of environmental destruction and inequality.

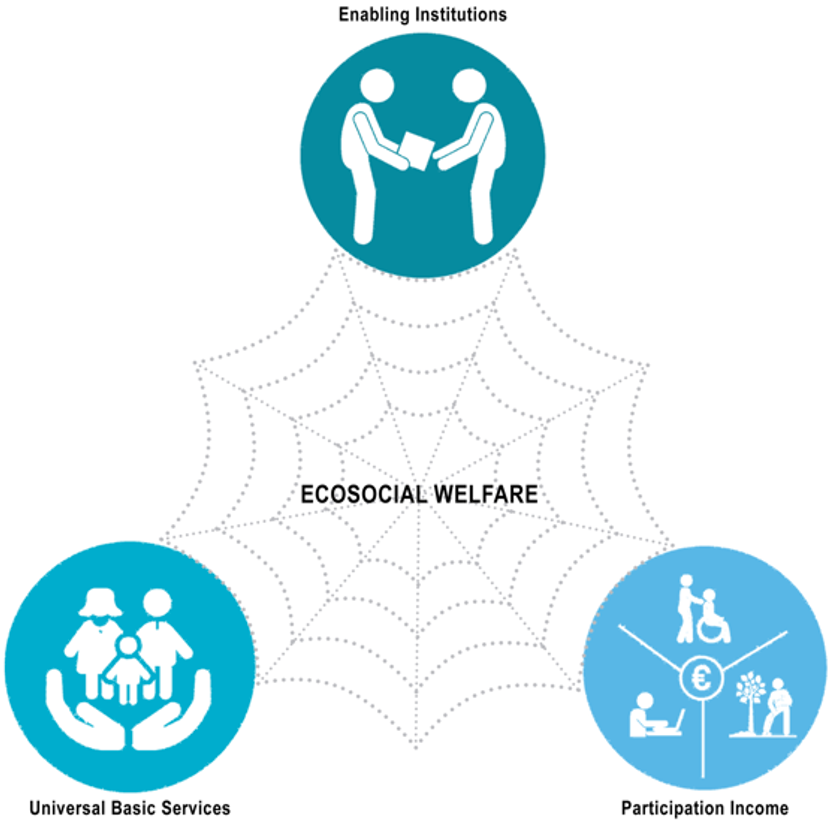

- Eco-social policies include the development of an enabling institutional infrastructure, universal basic services and a participation income.

- Any path to an eco-social welfare system requires the deepening and widening of democracy as well as the mobilisation of citizens.

In December 2022, the UK’s first new coalmine in over thirty years was approved to be opened in Whitehaven, Cumbria at a cost of 165 million GBP. This followed debates, which included public objections on environmental grounds. The mine will produce 2.8 million tonnes of coking coal and 400,000 tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions annually (the equivalent of 200,000 polluting cars) (Harvey, 2022). This demonstrates the complexity of negotiating highly financialised and commodified global systems with the knowledge of inevitable environmental and human damage.

Environmentally harmful patterns are leading us towards catastrophe and crisis, which can only offer opportunities for transformation if people are ready to act accordingly. The case for transformation is clear for multiple themes: inequality, socio-economic justice, health and well-being, social reproduction and democratic participation. Knowledge producers and policy makers urgently need to prompt social and institutional imagination and ensure that we know what we need to do when the opportunity of crisis arises. Alternatives need not be highly developed; they do not need to be policy blueprints or detailed maps. But they need to be inclusively imagined and articulated before the crisis emerges. This requires civil society to be ready now with ideas and capacity, and to be a space for agency and mobilisation (Levi, 2020). The inclusive political strategy for making this alternative happen requires a deepening and widening of democratic participation. This short article suggests a viable alternative: an eco-social welfare future that addresses the dual challenge of environmental destruction and inequality. This is consistent with a smart and equitable reset that integrates distributive and equity-weighted outcomes.

Interrelated problems can benefit from conjoined solutions. Environmental degradation and inequality are different sides of the same coin and can be addressed simultaneously. Inspired by Polanyi (1944), a fruitful way of understanding social policy is as a reaction and a decommodifying response to capitalism’s unrelenting commodification of labour, land and money. Recent research provides clear analyses integrating ecological and social arguments for a new eco-social future, including the transformational potential of specific social policy reform proposals across institutions, services and income supports. The challenge is to redistribute and support work, income, time and democratic participation in a post-growth society and economy, as part of wider systemic change (Hirvilammi and Koch, 2020).

An ecologically oriented social model demands a fundamental overhaul of existing welfare trajectories. A variety of policies are needed but three primary policies can underpin eco-social transformation. While market production and exchange remain, the trio of enabling institutions, universal basic services and participation income prioritise reciprocity and redistribution and maximise our social interdependence and capacity for mutual aid.

Source: Murphy M.P. (forthcoming), Creating an Ecosocial Welfare Future, (Bristol Policy Press, May 2023)

Institutions

An enabling institutional infrastructure can enhance the ecosystem of people’s lives and limit our collective dependence on the market to deliver core services and support. New institutions can promote new norms or revive old ones. Enabling institutions can be an active tool for a just transition by countering individualism, competition, consumption and selfishness, and by enhancing greater balance through reciprocity, collective freedom, interdependence, collaboration and participation.

Services

A foundational economy is a network of provisioning systems for satisfying basic and essential needs (Coote, 2022). Collective needs can be met through a system of universal basic services (Coote and Percy, 2020). Reducing collective consumption offers the best potential to reduce emissions and safeguard natural resources while also being key to more equal outcomes. There should be a diversity of providers, but the state can serve as an important enabler of such services through the provision of a regulatory framework and funding for a plurality of providers across public, social and private sectors. Care services are a priority but so too are health, education and housing, while environment, transport and recreation have much to offer in terms of sustainability.

Income

Participation income is social assistance reformed by reducing means-testing while retaining the reciprocity norm so it can only be paid to those who contribute to the society or community in some way (Hiilamo, 2022). A minimum income guarantee in the form of participation income can enable participation in socially useful activities and life choices consistent with a post-growth world that values and supports care, reciprocity, mutual interdependence and democracy (Jones and O’Donnell, 2018; Hiilamo and Komp, 2018). Decommodification deemphasizes the market and is central to reimagining the concept of income support in a form that breaks traditional notions. Reciprocal income support in the form of a participation income – more generous than contemporary social assistance payments – can enable and socially value unpaid but important work (e.g., care) and free up time for activities that have social and ecological worth. Some pandemic-era income supports offer useful templates (McGann and Murphy, 2023).

While there is no single pathway to making eco-social welfare happen, all pathways require two dimensions: deeper and wider democracy (i.e., more equalising structures) and mobilised citizens (i.e., more agentic power). Necessity is the mother of coalition (Folbre, 2020). Various movements, including those seeking gender, climate and economic justice need to coalesce to pressure for eco-social welfare (Jones and O’Donnell, 2018). At every level, whether in ideas, language or imagination, collective mobilisation and inclusive participation are needed to build our transformative power. Weaving a web of cooperation and collective mobilisation across relevant political and civil society campaigns, as well as maximizing various forms of power – insider, outsider and power within, with, to and for – requires the support of political elites who possess dominant forms of power (Wainwright, 2018). Such a transformative democracy is a high-energy democracy, the combined power of which can re-regulate the disembedded economy to better serve the needs of society and our endangered planet (Ungar, 2009).

Knowledge producers and policymakers can promote emerging eco-social thinking, monitor policy trends towards such alternatives and support research to better understand how transitions towards alternatives can be democratically accelerated.

Have you seen?

Transition-proofing welfare states – how should the EU go about it?

Public support for eco-social policies, the Swedish case

Protecting the climate without causing energy poverty

Workdays for future? How labour market policies can promote a climate-friendly world of employment

References

Coote, A. (2022) The case for a Social Guarantee: Universal access to life’s essentials. Brussels: Heinrich Boll-Stiftung.

Coote, A. and Percy, A. (2020) The Case for Universal Basic Services. London: Polity.

Gough, I. (2017) Heat, Greed, and Human Need: Climate Change, Capitalism, and Sustainable Wellbeing. Northhampton: Edward Elgar.

Folbre, N. (2020) The Rise and Decline of the Patriarchal Systems: An Intersectional Political Economy. New York: Verso.

Harvey, F. (2022) 'UK's first new coalmine for 30 years to get go-ahead in Cumbria', The Guradian, 7 December. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/dec/07/uk-first-new-coalmine-for-30-years-gets-go-ahead-in-cumbria (Accessed: 19 Dec 2022).

Hiilamo, H. and Komp, K. (2018) 'The case for a participation income: Acknowledging and valuing the diversity of social participation', Political Quarterly, 89(2), pp. 256-61.

Hirvilammi, T. and Koch, M. (2020) 'Editorial: Sustainable welfare beyond growth;, Sustainability, 12(5), pp. 18-24.

Hogan, J., Howlett, M. and Murphy, M.P. (2021) 'Re-thinking the coronavirus pandemic as a policy punctuation: COVID-19 as a path-clearing policy accelerator', Policy and Society, 41(1), pp. 40-52.

Jones, B. and O’Donnell, M. (2018) Alternatives To Neoliberalism: Towards Equality and Democracy. Bristol: Pluto Press, pp. 227-44.

Levi, M. (2020) ‘Frances Perkins was ready!’, Social Science Space. Available at: https://www.socialsciencespace.com/2020/03/frances-perkins-was-ready/ (Accessed: 10 December 2022).

Mandelli, M. (2022) 'Understanding eco-social policies: a proposed definition and typology', Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 28(3), pp. 333–348.

McGann, M. and Murphy, M.P. (2021) ‘Income support in an Eco-Social State: The Case for Participation Income’, Social Policy and Society, 22(1), pp. 16-30.

Polanyi, K. (2001) [1944] The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. Boston: Beacon Press.

Unger, R. (2009) The Left Alternative. London: Verso.

Wainwright, H. (2018) A New Politics from the Left. London: Polity.

….

Mary Murphy is Professor in the Department of Sociology, Maynooth University, with research interests in eco-social welfare, gender, care and social security, globalisation and welfare states, and power and civil society. She co-edited The Irish Welfare state in the 21st Century Challenges and Changes (Basingstoke, Palgrave, 2016) and authored the forthcoming Creating an Ecosocial Future (Policy Press, May 2023). An active advocate for social justice and gender equality, she was appointed to the Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission (2013-217) and is now a member of the Council of State.

The facts, ideas and opinions expressed in this piece are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO or any of its partners and stakeholders and do not commit nor imply any responsibility thereof. The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this piece do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.