The following article is authored by Rahul Matthan and Shreya Ramann.

- Data governance regimes have created highly protected and siloed ecosystems that present disproportionate barriers for vulnerable communities who cannot gain access to their own data needed for services.

- Break open data silos and correct asymmetries in the data market to empower individuals and widen access to essential services.

- Employ India’s Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture (DEPA) as a global template to build standardised, secure, seamless and inclusive data empowerment solutions across jurisdictions.

Today, access to basic resources such as financial services, healthcare, communication, education and employment involves the collection of personal information in relation to the service. As a result, users can get the most out of these services when they are able to easily access, aggregate and transfer their data to service providers.

Data governance policies have typically centred around prescribing which actions can be taken with user data, requiring user consent before such actions are taken (Matthan and Ramann, 2022). Business incentives and proprietary structures, combined with an ecosystem that promotes data protectionism, have led to strict walls being created around personal data – to the extent that individuals have no way of accessing and using their own data in a simple manner. Institutional policies promoting confidentiality and privacy lead to risk aversion and prohibitive costs associated with change (Balsari et al., 2020), particularly in sectors dealing with sensitive information like healthcare and financial services. Entities who collect personal data make accessing this data a cumbersome and complex process, often requiring individuals to undertake extensive paperwork, manual filings and in-person visits to service provider offices. Enabling this data to be directly transferred to other entities is also difficult, and in many cases not technologically feasible due to a lack of standardisation and differing formats for data storage (NITI Aayog, 2020).

Data governance priorities across many jurisdictions are now shifting towards improved data availability and access (Kak and Sacks, 2021). By breaking data out of silos, access to resources and services can become broader and more equitable. This is because individuals with access to digital identification and digital payments are likely to have generated vast amounts of transaction data or digital trails, held with various service providers. If these individuals are granted access to their digital trails, they can leverage them as ‘information capital’ (Tiwari et al., 2023) to avail a variety of benefits. These solutions are especially beneficial for individuals from vulnerable groups who have no other means of accessing various services due to a dearth of formal data.

Taking an example from the financial sector, individuals from lower socio-economic backgrounds and small businesses may not have a credit history or own capital assets, which are prerequisites to access a variety of financial services including loans. However, providing them with access to their digital trails, including transaction history, purchase history or tax filings, can help them prove creditworthiness through alternative means. Open banking initiatives introduced in the UK, EU, Australia and India are setting the stage to restore customer autonomy over financial data (Bank for International Settlements, 2019).

‘Information capital’ can also be used to empower workers in the informal sector, who often lack formal documentation in recognition of their skills or past employment. The ability to port credentials for educational qualifications, skills training or work experience between institutions and employers returns control to job applicants, who can provide verified documentation in support of their application.

The healthcare sector offers another strong use case for data access and transfer. Medical treatment often involves multiple service providers, including laboratories, imaging centres, hospitals, pharmacies and insurance companies, whose access to each set of records involves high costs and time-consuming paperwork (Balsari et al., 2020). These barriers disproportionately impact the ability of vulnerable communities to retrieve their medical records, leading to limited, inadequate or delayed treatment. The ability to transfer health data across service providers can address such issues by widening the net of individuals who can benefit from the full range of healthcare services, which in turn can significantly improve health outcomes. Overall, having access to personal health records is a proven tool for patient empowerment (Hägglund et al., 2022).

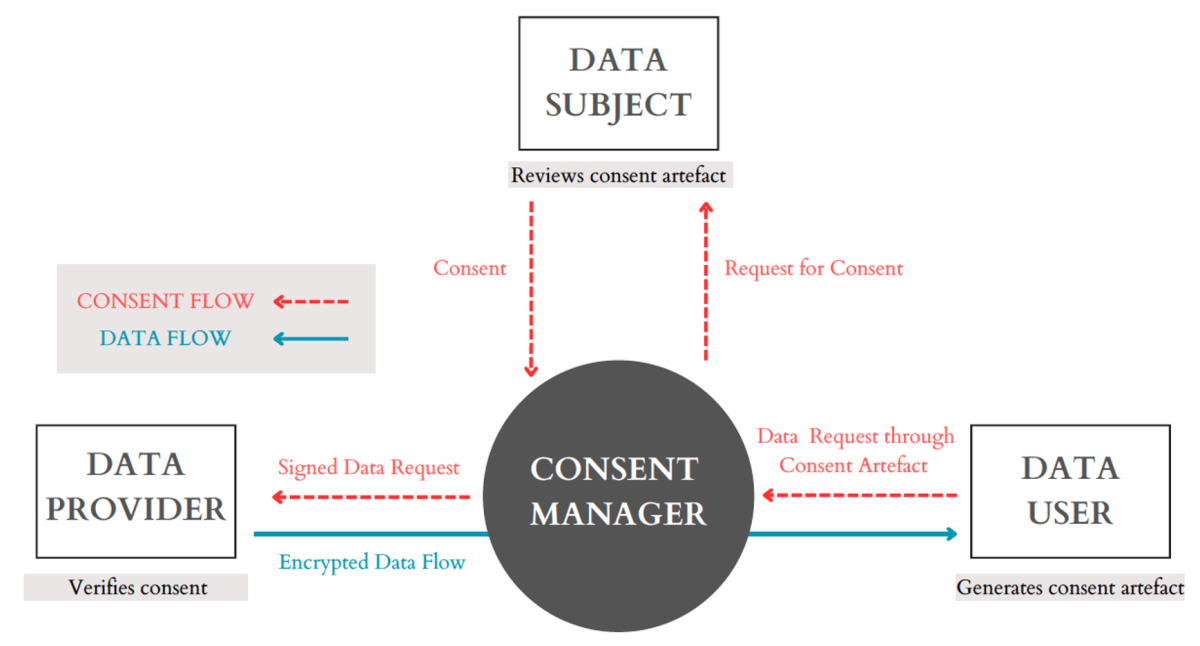

India’s Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture (DEPA) is one example of an operational and replicable data exchange framework that makes it possible to implement this sharing across a range of sectors and in different contexts. Using a consent-based data-sharing model, DEPA allows data subjects, or individuals with digital trails, to request access to their data from service providers, and provides them with a means to consent to data sharing between service providers (illustrated below). This is facilitated by intermediaries known as consent managers.

As a first step, an individual provides the consent manager with a list of third parties (data providers) who have access to their data and with whom they have an existing relationship. Consent managers then establish links with the data providers to enable the retrieval of data in real time. DEPA creates two distinct processes – one for the collection of consent and another for the corresponding flow of data (Matthan et al., 2023) – as described below:

- Consent flow: Third-party service providers (data users) initiate data requests by sending the consent manager a machine-readable ‘consent artefact’. The consent artefact records the details of a data request including the specific categories of data, the purpose of the request, the time period for which it is required, etc. The data subject reviews these details and provides their consent to the consent manager. Consent is recorded in a digitally signed request for data, which the consent manager sends to the data provider.

- Data flow: Data providers verify the user consent provided for the data request and accordingly send the required information to the data user via the consent manager.

This segregation of processes means that privacy and security are built into the system. Data providers are only involved in the data flow and have no visibility of to whom this data is provided and why. They are only required to verify that the data subject has consented to the data request. Similarly, consent managers are primarily involved in obtaining consent from the user. All data flows are encrypted, leaving the consent manager data blind with no ability to access any user data.

DEPA has been successfully implemented in India’s financial sector to improve access to financial services. Consent managers, known as Account Aggregators (AA), are registered entities responsible for facilitating consent-based data sharing between banks, insurance companies, pension funds and entities regulated by the securities regulator. According to the latest findings, more than 1.1 billion bank accounts have been linked to the AA ecosystem and 3.28 million users have shared their data using an AA (Ministry of Finance, Government of India, 2023), making DEPA the largest open banking initiative in the world. DEPA is also being deployed in the healthcare sector to enable data transfers between medical facilities, and between medical facilities and insurers for the simplified filing of health insurance claims. Blueprints for deployment in employment and education are also in development.

Data exchange solutions like DEPA are effective in breaking open data silos and correcting the asymmetry that exists in the data market today. By giving teeth to data access and portability rights, they enable service providers to rely on entirely new metrics when assessing potential users, thereby opening their markets to the underserved. Policy makers should employ DEPA principles and core components as a global template to build standardised, secure, seamless and inclusive data empowerment solutions across jurisdictions.

Have you seen?

Digital Public Infrastructure – lessons from India

Data as markets – it is time to talk (re)distribution

Data equity – there is no hiding

References

Balsari, S. et al. (2018) ‘Reimagining Health Data Exchange: An application programming interface–enabled roadmap for India’, Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(7). doi:10.2196/10725.

Bank for International Settlements (2019) Report on open banking and application programming interfaces (APIs). Available at: https://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d486.htm (Accessed: 19 September 2023).

Hägglund, M. et al. (2022) ‘Patient empowerment through online access to Health Records’, BMJ [Preprint]. doi:10.1136/bmj-2022-071531.

Kak, A. and Sacks, S. (2021) Shifting Narratives and Emergent Trends in Data-Governance Policy, Paul Tsai China Center, Yale Law School. Available at: https://law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/area/center/china/document/shifting_narratives.pdf (Accessed: 19 September 2023).

Matthan, R. and Ramann, S. (2022) India’s Approach to Data Governance, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/2022/08/31/india-s-approach-to-data-governance-pub-87767 (Accessed: 19 September 2023).

Ministry of Finance, Government of India (2023) Economic Survey of India 2022-23. Available at: https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/economicsurvey/ (Accessed: 19 September 2023).

Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship (2019) Adopting e-Credentialing in the Skilling Ecosystem - v1.0, Bharat Skills. Available at: https://bharatskills.gov.in/pdf/ESCS/Electronic_Skill_Credential_Standard_v1.0.pdf (Accessed: 19 September 2023).

NITI Aayog (2020) Data Empowerment And Protection Architecture – Draft for Discussion. Available at: https://www.niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2020-09/DEPA-Book.pdf (Accessed: 18 September 2023)

Tiwari, S., Packer, F. and Matthan, R. (2023) Data by People, for People, International Monetary Fund. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2023/03/data-by-people-for-people-tiwari-packer-matthan (Accessed: 18 September 2023).

….

Rahul Mathan is a partner at Trilegal, a law firm in India, where he heads the technology practice group.

Shreya Ramann is a senior associate at Trilegal and is part of the technology practice group.

The facts, ideas and opinions expressed in this piece are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO or any of its partners and stakeholders and do not commit nor imply any responsibility thereof. The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this piece do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.