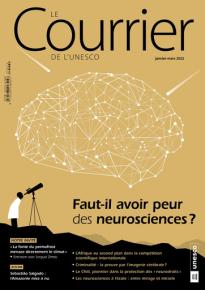

ثقافة | تربية | علوم وتكنولوجيا | المناخ والبيئة | المجتمع

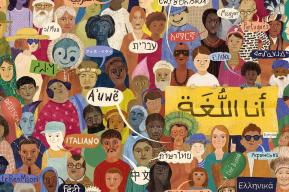

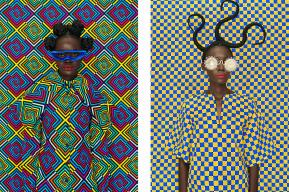

أدب الطفولة والشباب، حكاية نجاح

من قال أنّ الأطفال لم يعودوا يطالعون؟ أكيد أنّهم ليسوا ناشري أدب الطفولة والشباب. فهذا القطاع الذي مثّل حوالي 12 مليار دولار في العالم في سنة 2023، يشهد أفضل حالاته اليوم، حيث ينتج النّاشرون والرسّامون والكتّاب المولعون كتبا مبتكرة وذات جودة عالية. وهنا، تستكشف لكم رسالة اليونسكو، من الرّباط إلى بيونس آيرس مرورا بمالبورن، العالم الزّاخر لهذا النّوع من الأدب المتناسب مع مستوى الطّفل.

Sylvie Serprix

تقرأون في هذا العدد

بودكاست

أفكار

خبراء يدلون بآرائهم حول القضايا المعاصرة

ضيوفنا

حوارات مع أصوات رائدة في العالم

طالع النّسخة الورقية من العدد الأخير للرسالة

أدب الطفولة والشباب، حكاية نجاح

أبريل-يونيو 2024

Shutterstock